The Sky's the Limit: Tim Angelone's Story

With the help of MetroHealth's nationally ranked rehabilitation team, this passionate skydiver achieved what he never thought was possible.

It was perfect, the way it began.

The sky was clear. The sun shining. The temperature heading into the 80s. A gentle breeze, 10 mph, out of the southwest.

August 20, 2016 was an ideal day for skydiving.

Even better, the jump – No. 224 for Tim Angelone – was the start of a bachelor party for one of his best friends, buddies jumping together just like they would a few weeks later when the groom and his groomsmen – dressed in tuxes – would parachute down to the bride and a field full of guests.

As the single-engine plane reached 13,000 feet over rural Medina County, the smell of jet fuel, just like always, got Tim’s adrenaline pumping, hiked his senses to hyper alert. Diving out of a plane, falling 150 miles an hour, then watching the world as he floated down under his blue and yellow stiped canopy made him feel more alive than anything else.

If you knew Tim, it was no surprise.

Growing up in Cleveland’s Slavic Village, he was the kid who’d climb up old iron bridges, who busted his face skateboarding, who once hung from a power line, not realizing how lucky he was that the wire wasn’t live.

After graduating from Cleveland Central Catholic in 2007, he joined the Navy and spent most of the next four years in Guam troubleshooting electrical problems on generators and other equipment. And after his honorable discharge, in 2012, he backpacked across Spain, enlisted in the Navy Reserve and took up skydiving. The guys he jumped with became fast friends. He’d found his tribe.

The next year, he was sworn in as a Cleveland Police officer and ended up in the Fifth District, half of a two-officer team responding to domestic violence calls, burglaries and murders.

He spent his spare time kayaking, hiking, paddle boarding, running ultramarathons. In between, he kept bees, selling the honey through his Cleveland Honey Bee Company.

But what he loved most was heading toward earth like he was that August morning, floating under an open parachute, what skydivers call a canopy, content and carefree as a bird.

Then Tim realized he was headed for a creek.

He couldn’t let the 20 or so people watching see him land in the muddy water. He had too much pride.

That was his first mistake.

Just 250 feet or so from the ground, Tim quickly pulled his left hand down to brake that side of the canopy, to do an about face, to turn away from the water.

He’d turned low – and gotten away with it – before. But this time, as soon as he turned, he knew he’d made another mistake – a big one.

He quickly picked up speed and started to spin. Instead of heading for the ground feet first, his belly was leading.

The altimeter inside his helmet was beeping faster and faster, telling him he was getting closer to the ground. Then it flatlined, like a hospital heart monitor in the movies.

As the ground hurtled toward him, Tim knew there was only one thing that might save him. With all the strength and speed he had, he yanked the parachute brake in each hand.

I’m going to hit the ground so hard, I won’t feel a thing, he thought as he sped toward a freshly planted soybean field.

I’m not going to survive this.

'It's Your Best Chance'

As Tim drifted back into consciousness, he could see he was hooked to a machine in a hospital room, feel the brace around his neck, couldn’t help but wonder how any human could endure this much pain.

He remembered hitting the ground, feeling that first jolt, a pain 5,000 times worse than anything he’d felt before; remembered his friends running toward him, looks of terror on their faces; remembered the Metro Life Flight crew telling him they were flying him to the closest hospital.

What scared him most were his legs. He couldn’t feel them.

I’m going to be in a wheelchair for the rest of my life, Tim thought. I’ll never walk again.

The details came later: His pelvis had broken away from his spine. His sacrum was cracked in half. He’d herniated discs in his lower back.

But a calm, kind-faced spine specialist at Summa Akron City Hospital told Tim he was going to put him back together again. It was surgery he performed all the time.

Let’s do it, Tim told the doctor. Then he took a deep breath. Please don’t let me die, he pleaded.

If you were going to die, the doctor said, it would’ve been earlier today.

On good days after that, Tim imagined himself hiking and kayaking and heading out for 30-mile runs.

On bad days, he lay in bed crying, sure he’d never run, never skydive, never walk again.

As his body healed that first week, Tim’s recovery team told him he had two choices: he could go to a rehab hospital where he’d get three hours of physical, occupational and other therapy a day, where he’d regain as much as possible as quickly as he could. Or he could go to a nursing home where the amount of therapy would be a third of that and recovery much slower.

They recommended MetroHealth’s Rehabilitation Hospital in Old Brooklyn.

It’s the best chance you’ll have of recovering, they told him. But you have to show you can do the work. You have to move. You just can’t lay in bed and waste away.

I want to heal, Tim blurted.

Moving is healing, they shot back.

It was Day 7 or so when two physical therapists showed up in his room, positioned a walker next to his bed, wrapped a transfer belt around his waist and, one guy under each arm, slowly raised him to his feet.

Tim cried out. Tears rolled down his face. This pain seemed worse than all the horrible pain that had come before it.

My back is breaking, he yelled.

Your body’s not breaking, one of the physical therapists told him. They just literally screwed you back together again.

Tim stood for maybe five seconds.

But he’d done it. He’d proved he was ready for intensive rehab.

The next day, an ambulance drove him to MetroHealth’s Rehabilitation Hospital. Quickly, his team pulled together a plan that had him going home. In four weeks.

Impossible, Tim said to himself, angry at how broken he was. I can’t feel the backs of my legs or my feet. I’m diapered. I can’t even get out of bed.

I’ll be in a chair the rest of my life.

'Maybe I Can Do This'

Physical therapy began on Day 1.

It consisted of Tim sitting in his wheelchair, tears streaming down his face, crying out in pain, while a physical therapist flexed his right foot, the better of the two.

It was all he could do.

But it was progress.

Within days, he was getting out of bed without the crane-like lift that hoisted him up in its giant sling. With the help of two or three nurses, he could sit up. But the pain of all that brought on panic attacks. So once he was up, he sat in a chair all day long until it was time to go to bed.

His mom or one of his sisters slept in a chair beside his bed every night. They bathed him, changed his diaper. And never stopped believing in him.

You’re going to make a full recovery, his mother would tell him whenever he’d panic or start crying.

All Tim could do was swear.

Do you see how I look? I’m lying in bed in a diaper.

Still, every day for three or four hours, he soldiered through physical therapy, occupational therapy and pain. There was so much pain.

Therapists worked with Tim for hours until he was moving his feet on his own, then his ankles and his knees.

Maybe I can do this, Tim thought. I’m getting out of bed now. I’m in a wheelchair, I’m making progress.

That was Week 1.

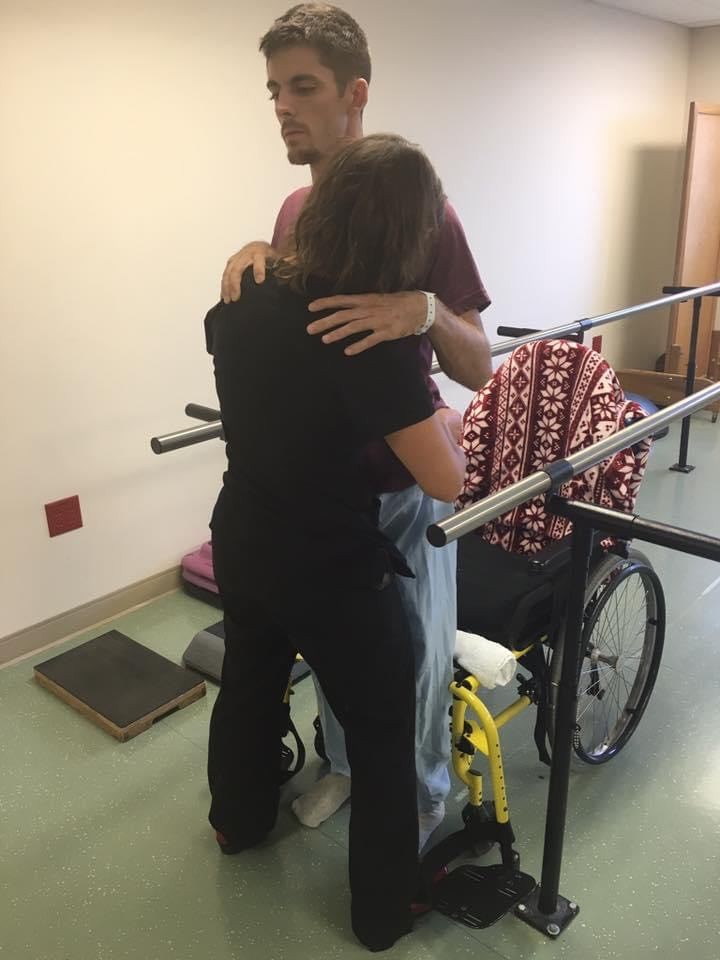

The next week he was standing. For five seconds, then 10, with therapists supporting him, one on each side. By the end of that week, he was taking his first steps, holding tight to the parallel bars in the gym. Maybe I will walk out of here one day, he thought.

By Week 3, he was walking the entire length of the parallel bars, a therapist with a wheelchair behind him, just in case. His balance was off, but he was doing it. He was climbing stairs, too, getting in and out of the car and shower in MetroHealth’s therapy gym, putting on his socks by himself.

His mom knew what she was doing. Say something enough times and people begin to believe it, even Tim. He had graduated from wheelchair to walker to cane to crutches. He was going to walk out of the hospital.

Then came Week 4.

Suddenly, in the middle of physical therapy, what felt like lightning bolts shot through Tim’s left foot and leg. He couldn’t walk.

Tim yelled. And swore. And cried. It felt like everything he had worked so hard for was gone.

But at the end of that week, he did go home.

His father brought honey he’d bottled from the fall harvest, a jar for everyone who had cared for Tim. There were hugs and all the encouragement a guy could want.

But Tim needed a wheelchair and his sister to get to the car.

And all the people he’d depended on every day? They weren’t going with him.

“The really amazing people were the nurses and aides and the people who delivered the food and, just literally, cared like you couldn’t imagine 24 hours a day,” Tim says now.

“I didn’t want to leave the place because they had taken such good care of me.”

Now, it was all up to him.

And he was scared.

'A Plan To Give Me My Life Back'

For hours a day, Tim was home alone with no one to talk to. No one to listen. No one who understood

His brother and a friend moved into his apartment to help, but they both had jobs. Tim had turned down offers from his mother and sisters. They’d already done so much.

He tossed his pain medication, too. Working as a cop, he’d seen plenty of drug addicts. He wasn’t about to become one. Without it, the aching kept him up at night. So he’d sleep during the day, wake late, wrestle his wheelchair down narrow hallways, fight to thread it through doorways, get angry, sulk.

Some days, he’d cry until he couldn’t cry anymore. Unless he was back at the hospital for outpatient therapy. He’d put on a smile for that.

After a while, his life wasn’t just turning dark, he was starting to like the dark. He didn’t want to see anyone, didn’t want to talk to anyone. What he wanted to do was die.

When he started planning how, he knew he was in trouble. He grabbed his walker, and with his mother at his side, hobbled back to MetroHealth, sat down with one of his doctors and, no smile this time, told him the truth.

“He listened – genuinely listened – to me that day,” Tim remembers. “Then he went into the hallway and found a group of people to help. They rallied around me. They came up with a plan to give me my life back.”

The MetroHealth team helped Tim realize he’d come off his pain medication way too fast. Like people on the street he’d seen so many times as a police officer, he was going through withdrawal.

Back on the right medication and in regular sessions with his rehab psychologist, Tim’s depression began to lift. He found himself crying less, sleeping more.

He began meditating, too. Took up yoga. Didn’t care if people saw him shuffle in with his cane as he headed to the gym. He started with stretches, moved up to lunges and squats, eventually worked out for more than 100 days straight.

Seven months after his surgery, he was back at work on light duty.

Nine months after, he was stronger than he’d ever been.

A month after that, he thought maybe he could backpack again.

Three weeks later, on August 7, 2017, Tim flew to Europe, met an old friend, and began to walk the northern route of the Camino de Santiago, The Way of St. James, hundreds of miles across Spain.

For some, the walk made famous in the movie “The Way” is a religious experience. For nearly everyone, it’s a journey of healing, growth and transformation.

After 40 days of hiking from sunrise to sundown, Tim’s nerve pain began to lift. His bladder started functioning again. His head was healing, too. The physical trauma and years of stressful police work were melting away.

“Life just got so simple,” he says, “I began to feel like a kid again.”

Fifty-three days after he took the first step, with 650 miles behind him, Tim flew back to Ohio and returned to desk work at the Cleveland Police Department. He got back to paddleboarding, camping and beekeeping, too, all the things he thought he’d never do again.

Except one.

It took a couple of years, but on November 4, 2019, Tim drove to Alliance, Ohio, with one of his closest skydiving friends, climbed into a plane, flew 10,000 feet in the air and made his first solo jump since the day he nearly died.

“It was the last thing that I felt like I wanted – and needed – to do to come full circle,” he says.

“When I jumped from that airplane on my own, I felt complete.”

And ready for a new journey.

He’s 31 now, still hiking or paddleboarding or backpacking or camping every week. Keeping his bees, too, selling honey at stores all over Northeast Ohio.

And he’s still working at the Cleveland Police Department.

But he’s taking on an additional role.

Now he’s part of a new Countywide Peer Support Program that helps any first responder in Cuyahoga’s more than 50 communities overcome the death of a co-worker or family member, a divorce -- any kind of physical, emotional or mental trauma.

It’s something Tim had already been doing. Whenever somebody needed to talk about their troubles, he was there. He’d made it through his moment of truth, come out on the other side, wanted everyone else to know they would, too.

But now, it’s official. Tim’s completed peer support training to help fellow first responders find the professional help they might need. And the program he’s helping start is seen as a model for other departments across the country.

“This is what gives me joy – talking to people who are going through the worst periods of their lives,” Tim says, “trying to provide a bit of hope when they might be lacking hope.

“Like I was.”

It was perfect, the way it began.

Tim Angelone is sure of that.

And the way it’s ending?

That’s perfect, too.

He’s even more sure of that.

“Life is pretty fantastic now,” he says.

“I just kind of feel like I was born again.”

'You Can't Do It Alone'

Recovery like Tim Angelone’s is what MetroHealth’s Rehabilitation Team works toward for every one of the hundreds of patients it cares for each year.

“We want to see every patient get back to what they really, really love,” says Dr. Victoria Whitehair, MetroHealth’s Medical Director of Inpatient Rehabilitation. “It’s what we hope for everybody.”

One big reason for that success? The hospital’s commitment to teamwork.

“A trauma like that is a major life event,” says Darcy Kosmerl, a MetroHealth physical therapist who continued working with Tim after his hospital stay. “It has to be addressed from multiple angles.”

At a minimum, that means patients are cared for by a physical, occupational and speech therapist; rehabilitation psychologist; social worker; case manager; rehabilitation-trained nurses; and, of course, a physiatrist, a doctor who specializes in physical medicine and rehabilitation.

“You can’t do it alone,” says Dr. Whitehair.

“Without every one of those team members, we can’t make it happen. It really takes the team working very closely. So we meet every day to talk about our patients, to look at their successes, their challenges, their barriers and how we’re going to address all of that.

“If each of us just works in our bubble, we can’t do what we need to do for the patient.”

Dr. Kip Smith, Tim’s Rehabilitation Psychologist, says the collaboration is like putting together a puzzle.

“If you don’t have every piece, you may not have a positive outcome,” she says.

“And the team isn’t just the MetroHealth team, it’s your church, it’s your family, it could be your employer.

“All those pieces have to be in place to have hope and see the future.

“That’s what we really do. We provide hope.”

And the team keeps providing that hope – sometimes for years.

“Nobody sees rehabilitation as ending when a patient goes home from the hospital,” Dr. Whitehair says.

“It is a journey. And the team is there with you, even after you leave.”

- Named a Best Physical Rehabilitation Center in 2020 by Newsweek

- Provides care in specialized units dedicated to stroke, brain injury and spinal cord injury

- Has the only Spinal Cord Injury Model System Center in Northeast Ohio

- Treats more medically complex patients than most rehabilitation hospitals in Ohio and the United States

- Cared for nearly 1,000 inpatients in 2020 with an average length of stay of 16 days

- Helped those patients recover from stroke (21%), brain injury (21%), joint replacements, broken bones or other traumatic injuries (21%), spinal cord injuries (18%) and burns or other illness or injury (19%)

Founded in 1837, MetroHealth is leading the way to a healthier you and a healthier community through service, teaching, discovery, and teamwork. Cuyahoga County’s public, safety-net hospital system, MetroHealth meets people where they are, providing care through five hospitals, four emergency departments and more than 20 health centers. Each day, our nearly 9,000 employees focus on providing our community with equitable healthcare — through patient-focused research, access to care, and support services — that seeks to eradicate health disparities rooted in systematic barriers. For more information, visit metrohealth.org.